THIS month marks the 365th anniversary of the execution of King Charles I. Here, historian Mark Muller paints a picture of this historic event, and explains its links with Haverfordwest.

On Tuesday, January 30, 1649, Charles waited patiently for four hours before walking from St James’s Palace to the execution site.

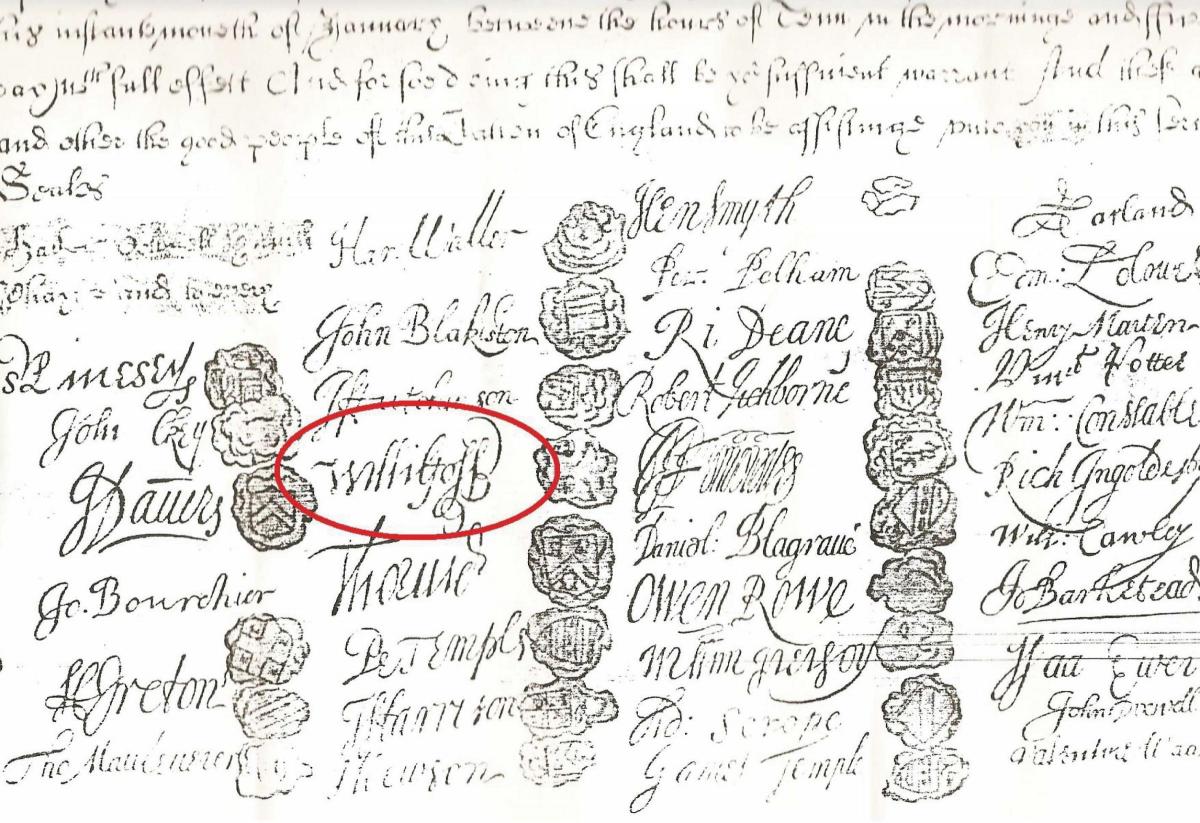

Of the 67 commissioners appointed as judges of the king, only 59 signed the death warrant, with some of these having to be persuaded. Even as late as the day before, several signatures were still required and some accounts report that Cromwell dragged one reluctant commissioner over to the table where the death warrant lay.

Such reluctance was not demonstrated by Colonel William Goffe.

The lives of the Goffe family were so remarkable as to be usually seen only in films or read in fiction.

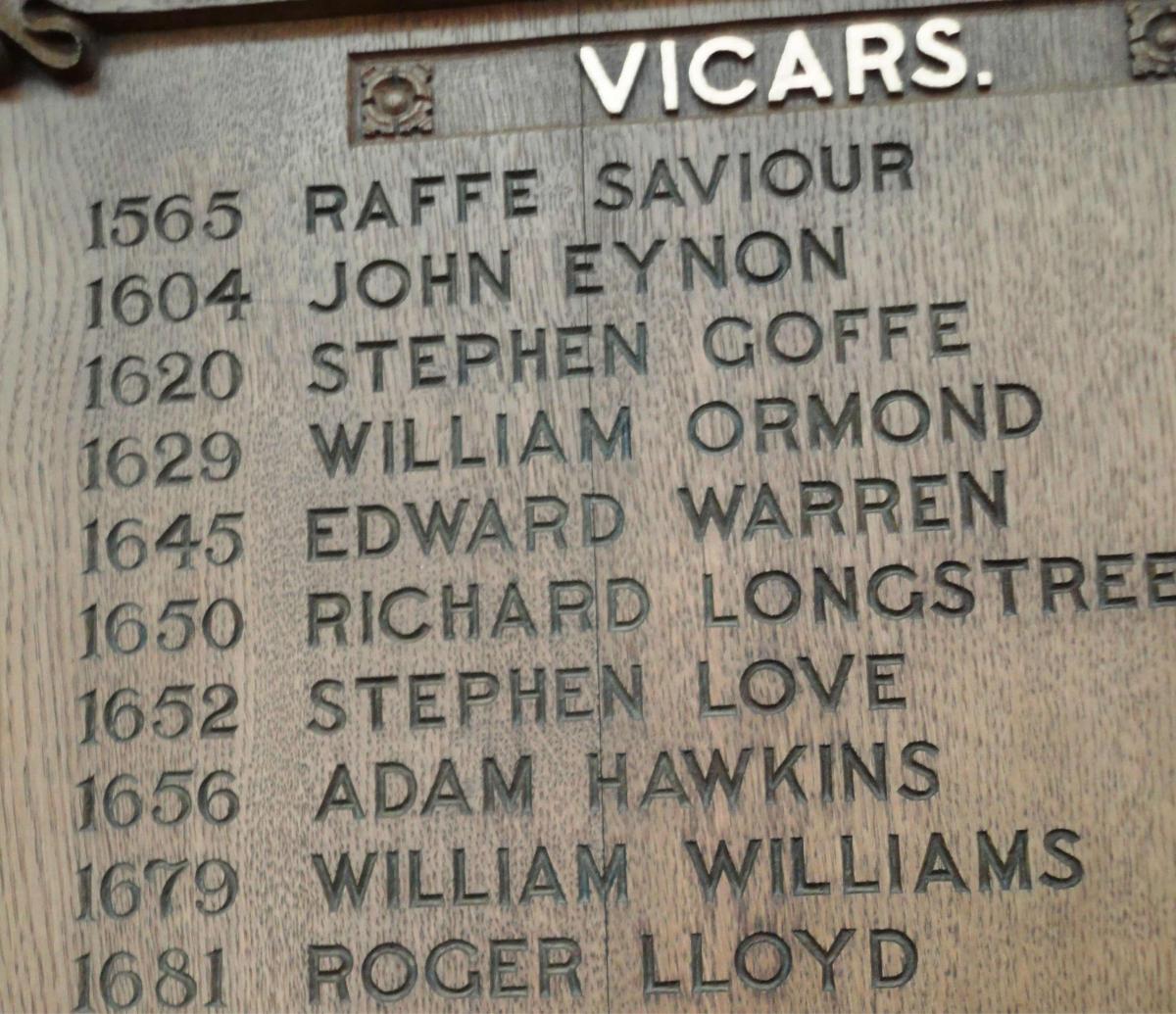

Stephen Goffe was the vicar at St Mary’s Church in Haverfordwest in 1620. Of his three sons - John, Stephen and William - at least William was born in the town.

He caught Cromwell’s eye not long after enlisting in the Parliamentary Army at the start of the Civil War and was soon promoted to colonel.

In 1648 he was prominent in a prayer meeting of the senior officers at Windsor, where it was decided to bring the king to trial. His description of the king as ‘that man of blood’ was a phrase that was to stick.

In the same year Goffe, along with other colonels who were to become regicides, took part in the siege of Pembroke Castle.

This seven-week operation under the command of Cromwell was in response to the actions of General Rowland Laugharne and colonels Poyer and Rice Powell, who had changed sides and activated a sequel to the Civil War, largely as a result of having received no pay.

Haverfordwest was used a base by Cromwell and Goffe spent time in his home town. The borough records contain the following entry:

‘Paid 1st June 1648 when Lt Coll Goffe came to town paid for a dinner bestowed on him and his company and for wine and beer and cyder £1 5s 6d’.

Powell surrendered Tenby Castle and Poyer and Laugharne were defeated at Pembroke after Cromwell sent for heavy artillery. The three were taken to London and condemned to death but in recognition of their earlier service for Parliament it was decided that only one would be executed and a child was used to draw lots out of a hat. Poyer was the unlucky one.

Six months later, Goffe signed the death warrant of Charles I. His signature appears as Willi Goff in the centre of the warrant, above that of Colonel Pride.

But this act was to come back and haunt them. On the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, an act was passed pardoning everyone who had fought against the king during the Civil War... except those who had signed the warrant. There followed an unremitting vendetta in which even those signatories who had died in the meantime were exhumed and their bodies hung, drawn and quartered.

Goffe was captured but escaped and managed to get to the New England colonies in North America.

Even there he was hunted by agents of Charles II but was helped by colonists and during an attack by Indians gave valuable assistance. He corresponded with his wife under the name of Stephenson and died in Hadley, Massachusetts in 1679. Hadley Historical Society wrote to me some years ago and advised me that they proudly had a ‘Goffe Street’.

But it doesn’t end there; William’s brother Stephen trained as a priest and became chaplain to Charles I. During the Civil War he became a secret agent for the Royalists and was prominent in negotiations on the king’s behalf when it became obvious that the war was lost. He fled to Holland with the future Charles II and it fell to him to reveal that the king had been executed. This he did by addressing the prince as ‘your Majesty’.

Another regicide, Thomas Wogan, was from Haverfordwest but his story will have wait for another article.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here