Murray Walker will be remembered as the undisputed voice of Formula One.

Walker’s unique, high-octane style – once described by Australian comic Clive James as “sounding like a man whose trousers are on fire” – is forever ingrained in British sporting culture.

From James Hunt’s 1976 championship triumph over Niki Lauda at a rain-lashed Fuji, to Ayrton Senna’s intense rivalry with Alain Prost and Nigel Mansell’s 1992 title triumph, Walker called it all in a remarkable broadcasting career which spanned 52 years.

Murray Walker was appointed an OBE in 1996 for his services to broadcasting and motor racing (John Stillwell/PA)

Murray Walker was appointed an OBE in 1996 for his services to broadcasting and motor racing (John Stillwell/PA)

When Damon Hill took the chequered flag at Suzuka to win the Japanese Grand Prix and become world champion in the early hours of an October morning in 1996, an emotional Walker cried: “I have got to stop because I have got a lump in my throat.”

It is those memorable words which will resonate among the motor racing community and generations of fans following his death at the age of 97.

Graeme Murray Walker was born in Birmingham to father Graham and mother Elsie on October 10, 1923. Graham was a prominent figure in motorcycling and enjoyed a 15-year career which culminated in him winning the prestigious Isle of Man TT race.

“You either loved what your father did or you loathed it,” Murray explained. “But my father was a great man, I was very fond of him, and I wanted to be like him.”

Happy 96th Birthday to Murray Walker! 🎂🎉

We asked for your favourite #JapaneseGP moments, and this was a popular one!👇

🎙"I've got to stop, because I've got a lump in my throat"

Murray Walker's unforgettable commentary as @HillF1 seals the 1996 championship in Japan 🏆 pic.twitter.com/cJsN2JlZi8

— Sky Sports F1 (@SkySportsF1) October 10, 2019

But before Walker could attempt to emulate him, he was conscripted into the British army, aged 18. Walker soon graduated from Sandhurst’s Royal Military College and went on to command a Sherman tank in the Battle of the Reichswald in World War Two.

Walker reached the rank of captain but left the army in the years following the war and turned his attention back to two wheels.

Although he was a decent motorcyclist, Walker was not in the same league as his father, and it would be the advertising world where he would first make his name. Walker retained his passion for motor racing by commentating at the weekends.

But when Hunt beat Lauda to the 1976 title, Walker’s life changed. The BBC ramped up its coverage and a relatively unknown advertising executive was handed the commentating duties.

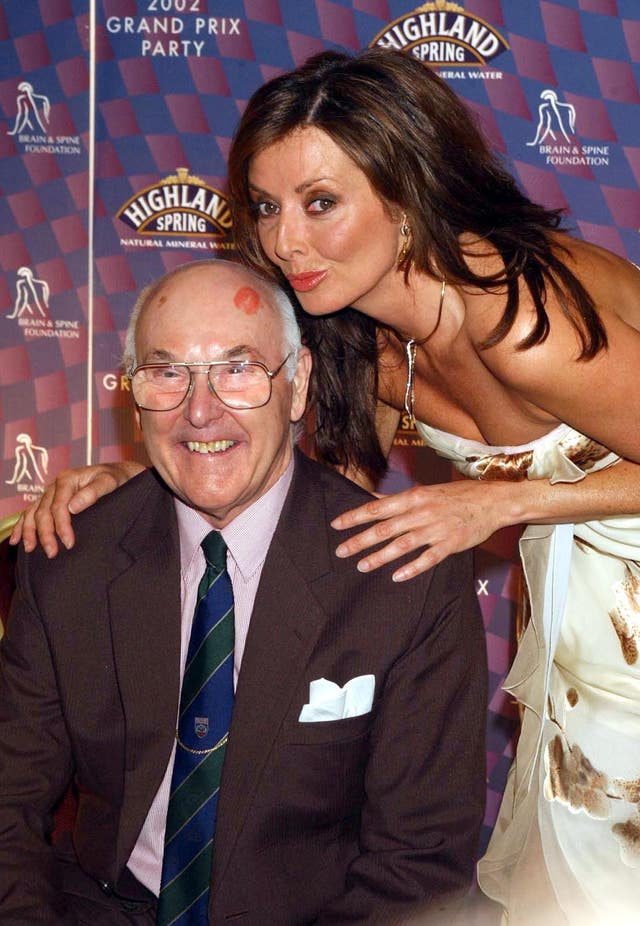

Murray Walker poses with television personality Carol Vorderman (Yui Mok/PA)

Murray Walker poses with television personality Carol Vorderman (Yui Mok/PA)

“Britain suddenly became aware of Formula One because of the glamorous, playboy image that James had,” explained Walker.

“The BBC decided they were going to do every race and they asked me to do it.

“I carried on doing both advertising and commentary jobs for four years until in 1982, when I was 60, I retired from the advertising business and then my broadcasting career started.”

As most would be winding down, Walker entered his seventh decade by beginning a second career which would see him become a household name.

Popular for his passion, Walker was the motor racing fan with a microphone.

When Mansell crashed out of the 1987 title decider in Australia, he yelled: “And colossally that’s Mansell.”

"AND COLOSSALLY THAT'S MANSELL!"

💔 for Red 5 but an iconic call from the inimitable Murray Walker 🎙️

What other dramatic pieces of @F1 commentary will always stick with you? #F1Rewind ⏪ #WeAreWilliams 💙pic.twitter.com/bxTWdxV0c4

— Williams Racing (@WilliamsRacing) April 1, 2020

As Michael Schumacher rammed into the back of David Coulthard at a rain-soaked Belgian Grand Prix in 1998, Walker shouted: “Oh, God!”

And when Frenchman Jean Alesi parked up at the side of the road after running out of fuel in Australia, Walker said: “You can see by the body language of the Benetton mechanics that they are ab-so-lute-ly furious. Oh Jean, you may well look a bit worried because you have got a major problem, sunshine.”

But, bizarrely, it was his mistakes – later nicknamed ‘Murrayisms’ – which earned him his status as a national treasure.

“There is nothing wrong with his car, except that it is on fire!” he once proclaimed.

“I’m ready to stop my startwatch,” he said on another occasion, while “unless I am very much mistaken – I am very much mistaken” later became the title of his autobiography.

Murray Walker with Martin Brundle (left) and Louise Goodman after ITV captured the broadcasting rights in 1997 (Rebecca Naden/PA)

Murray Walker with Martin Brundle (left) and Louise Goodman after ITV captured the broadcasting rights in 1997 (Rebecca Naden/PA)

At the BBC, Walker was partnered by Hunt for 13 years before his death in 1993. The clash of personalities – Walker a consummate professional compared to Hunt’s rather laid-back approach – won over the public.

“James didn’t care what people thought,” said Walker of their odd-couple relationship. “He was an extrovert, a showman, he drank too much, smoked too much and womanised like there was no tomorrow.

“He could be the most arrogant, overbearing person you would ever meet in your life and he frequently was. But there was a nice person hiding inside and, when he retired from racing, the nice chap took over.”

When Hunt died and Formula One headed to ITV in 1997, Walker, who had been appointed an OBE the previous year for his services to broadcasting and motor racing, teamed up with Martin Brundle, whom he would work alongside for five seasons before his final race at the US Grand Prix in 2001. He was 77 when he stopped.

Following his retirement, Walker said he was “not going to be a pathetic old hanger-on in the paddock”, and he was true to his word with only fleeting appearances since.

Walker is survived by his wife Elizabeth.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here